How to write web apps, Part 1

A Detailed Primer with Typescript & React

In all my years as a developer I’ve never encountered a wilderness as overwhelming as The JavaScript World. It’s a world of bewildering complexity, where making a very simple project seems to require installing numerous tools, editing several text files that connect all those tools together, and running a bunch of terminal commands. There are some tools that try to hide the complexity from you, with varying degrees of success - but as long as those tools don’t have universal adoption, these tools just seem to me like even more things you have to learn on top of everything else.

For me, the biggest source of irritation is that most tutorials assume you are already familiar with the ecosystem so they don’t bother to explain the basics. To make this worse, many tutorials try to push a bunch of extra tools on you - webpack, bower, nvm, redux, etc. - with little explanation. It’s ironic because JavaScript itself is already installed on virtually every computer in the world, including phones. Why should writing an app the “professional” way have to be so complex compared to writing an html file with some Javascript code in it?

If, like me, you have an innate need to understand what is going on - if you can’t stand blindly copying commands into terminals and text files, if you want to make sure you need a tool before you install it, if you’re wondering why your npm-based project is 50MB before you’ve written your first line of code - welcome! You’ve come to the right place.

On the other hand, if you wanted to start programming in 5 minutes flat, I know a trick for that: skip this article and start reading about Approach A in Part 2, then go straight to Part 4. Or if you think I’m giving you too much information, just skip the parts you don’t want to learn about right now.

In this tutorial I will assume you have some programming experience with HTML/CSS and Javascript, but no experience with TypeScript, React, or node.js. I’ll give you an overview of the JS ecosystem as I understand it, I’ll explain why I think React (or Preact) with TypeScript is your best bet for making web apps, and I’ll help you start a project without unnecessary extras. In part 2, we will discuss how and why to add a couple of extras to your project, if you decide you want them.

Part 1: Overview of the JavaScript Ecosystem

For many programming languages, there’s a certain way of doing things that everybody knows about. For example, if you want to make a C# app, you install Visual Studio, create a Windows Forms project with a few mouse clicks, click the green “play” button to run your new program, and then start writing code for it. The package manager (NuGet) is built-in and the debugger Just Works. Sure, it might take a few hours to install the IDE, and WPF is about as fun as waterboarding, but at least getting started is easy. Except if you’re not in Windows, then it’s totally different, but I digress.

In JavaScript, on the other hand, there are so many competing libraries and tools for almost every aspect of the development process, the barrage of tools can become overwhelming before you write your first line of code! When you go Googling “how to write a web app”, every web site you visit seems to give different advice.

Thanks draw.io for the diagramming tool!

The one thing most people seem to agree on is using the Node Package Manager, npm, for downloading Javascript libraries (both server-side and browser-only). But even here, some people are using yarn, which is npm-compatible, or possibly bower.

npm is bundled with Node.js, a web server you control entirely with Javascript code. npm is tightly integrated with Node; for example, the npm start command runs node server.js by default. Even if you were planning to use a different web server (or to use no web server and just double-click an html file), everybody seems to assume you’ll have Node.js installed, so you may as well go ahead and install node.js which gives you npm as a side-effect. Node.js isn’t just a web server; it can also run command-line apps written in JavaScript. In that sense, the TypeScript compiler is a Node.js app!

Beyond npm you have several choices:

Which flavor of Javascript do you want?

The official name of JavaScript is actually ECMAScript, and the most widely-deployed version is ECMAScript 6 or ES6 for short. Old browsers, notably Internet Explorer, support only ES5. ES6 adds lots of useful and important new features such as modules, let, const, arrow functions (a.k.a. lambda functions), classes, and destructuring assignment. ES7 adds a few more features, most notably something called async/await.

If you don’t need to support old browsers and your code isn’t very large, running your code directly in the browser is an attractive option because you don’t have to “compile” your JavaScript before opening it in the browser. But there are many reasons to use a compile step:

- If you need to support old browsers, you’ll want a “transpiler” so you can use new features of JavaScript in old browsers (a transpiler is a compiler whose output code is a high-level language, in this case JavaScript). I would guess the most popular transpiler is Babel, with TypeScript in second place.

- If you want to use the popular React framework (but without TypeScript), you’ll probably be writing “JSX” code - fragments of XML inside JavaScript code. JSX is not supported by browsers and so requires a preprocessor (typically Babel).

- If you want to “minify” your code so it uses less bandwidth (or is obfuscated), you’ll need a “minifier” preprocessor. Popular minifiers include UglifyJS, JSMin and the Closure Compiler.

- If you want type checking or high-quality code completion (also known as IntelliSense), you’ll want to use TypeScript, a superset of JavaScript (meaning every JavaScript file is also a TypeScript file… ostensibly). TypeScript supports both ES7 features and JSX, and its output is ES5 or ES6 code. When TypeScript and JSX code are used together, the file extension must be

.tsx. Some people are using a different language, similar in concept to TypeScript, called Flow. - If you don’t like JavaScript, you could try a totally different language that transpiles to JavaScript, such as Elm, ClojureScript or Dart.

It’s possible to automate compiling so that your code is compiled whenever you save a file.

This tutorial uses TypeScript, a superset of JavaScript with a comprehensive type system. The benefits of TypeScript are that

- You get compiler error messages when you make type-related mistakes (instead of discovering mistakes indirectly when your program misbehaves). In IDEs such as Visual Studio Code your mistakes are underlined in red.

- You can get refactoring features. For example, in Visual Studio Code, press F2 to rename a function or variable across multiple files, without affecting other things that have the same name.

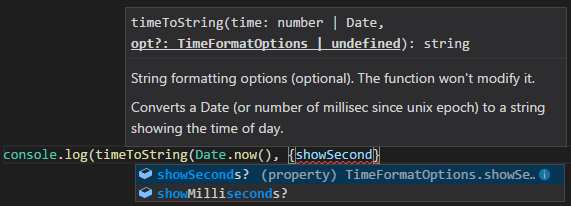

- Types allow IDEs to provide code-completion popups, also known as IntelliSense, which makes programming much easier because you don’t have to memorize all the names and expected arguments of the functions you call.

To play with TypeScript without installing anything, visit its playground.

Client versus server

Your can run code in a client (front-end browser), a server (Node.js back-end), or both. The client is not under your control; the user might use Firefox, Chrome, Safari, Opera, Edge, or in the worst case, Internet Explorer. For security reasons, keep in mind that the user can modify a browser’s behavior using browser extensions or the F12 developer tools. You can’t even be sure that your code is running in a real browser.

Developers used to rely on the jQuery library to get consistent behavior in different browsers, but these days you can rely on different browsers to behave the same way in most cases (except perhaps IE).

In this tutorial we’ll run all the important code in the browser, but we’ll also set up a simple Node.js server to serve the app to the browser. Many other servers are available, such as Apache, IIS, or a static server like Jekyll, but Node.js has become a sort of de-facto standard, likely because Node.js and npm are bundled together.

User Interface frameworks

HTML and CSS alone are great for plain-old articles with images, or simple forms. If that’s all you’re doing, there’s probably no need for JavaScript at all. CSS can even do some things that once required JavaScript, such as pull-down menus, pages that completely reformat themselves for small/mobile browsers or printing, and animations.

If you need something more complex than that, or if your pages are generated dynamically from raw data, you’ll probably want to use JavaScript with an optional user-interface library or framework. This article will cover React, which has earned a position as the most popular UI framework, and its little cousin Preact. The “large” popular alternatives include Angular 2 and Vue.js, while the “small” ones include D3, Mithril and an old classic called jQuery. If your web server runs JavaScript (Node.js), you can run React on the server to pre-generate the initial appearance of the page.

Build tools

Several tools for “building” and “packaging” your code are available - webpack, Grunt, Browserify, Gulp, Parcel - but all these things are optional and I’ll show you how make do with npm and, if you want, Parcel or webpack.

CSS Flavors

In this series we’ll use plain CSS, but if you’re going to have a compile step anyway, you might want to try SCSS, an “improved” derivative of CSS with extra features. Or you could use SASS, which is conceptually identical to SCSS but has a more concise syntax. Either way you’ll need the Sass preprocessor. And as always in the JavaScript World, there are a bunch of alternatives, notably LESS.

Unit testing

The popular unit testing libraries are Mocha and Jasmine. See here for more. npm has a special command for testing, npm test (which is short for npm run test).

Other libraries

Other popular JavaScript libraries include lodash, Ramda, underscore, Redux and GraphQL. The most popular linting utility is eslint. Bootstrap is a popular CSS library but it requires a JavaScript part (and it’s really SASS, not CSS).

When you see $ in JavaScript code, it typically refers to jQuery; when you see _ it typically refers to either lodash or underscore.

And perhaps it’s worth mentioning popular templating libraries: Jade, Pug, Mustache and Handlebars.

Non-web apps

I won’t say anything more about this, but TypeScript and JavaScript can be used outside the web. With Electron you can write cross-platform desktop apps, and with React Native you can write JavaScript apps for Android/iOS that have a “native” user interface. You can also write command-line apps with Node.js.

Module types

For the longest time all JavaScript code ran in a single global namespace. This caused conflicts between unrelated code libraries, so various kinds of “module definitions” were invented to simulate what other languages call packages or modules. Node.js uses “CommonJS” modules, which involves a magic function called require('module-name') to import modules and a magic variable called module.exports to define modules. To write modules that work in both browsers and Node.js, one can use UMD modules. Modules that can be asynchronously loaded use AMD.

ES6 introduced a module system involving import and export keywords, but Node.js and some browsers still don’t support it. Here’s a primer on the various module types.

Polyfills & Prototypes

As an experienced developer, I can think of only two words (other than the names of libraries & tools) that are used only in JavaScript Land: polyfill and prototype.

Polyfills are backward-compatibility helpers. They are pieces of code written in JavaScript that allow you to use new features in old browsers. For example, the expression 'food'.startsWith('F') tests whether the String 'food' starts with F (for the record, that’s false - it starts with f, not F.) But startsWith is a new feature of JavaScript that is not available in older browsers. You can “polyfill it” with this code:

String.prototype.startsWith = String.prototype.startsWith ||

function(search, pos) {

return search ===

this.substr(!pos || pos < 0 ? 0 : +pos, search.length);

};

This code has the form X = X || function(...) {...}, which means “if X is defined, set X to itself (i.e. don’t change it), otherwise set X to be this function.” The function shown here behaves the way startsWith is supposed to.

Even some advanced browser features have polyfills. Have you heard of WebAssembly, which lets you run C and C++ code in a browser? There’s a JavaScript polyfill for it!

This code refers to one of the other unique things about JavaScript, the idea of prototypes. Prototypes correspond roughly to classes in other languages, so what this code is doing is actually changing the definition of the built-in String data type. Afterward when you write 'string'.startsWith() it will call this polyfill (if String.prototype.startsWith was not already defined). There are various articles out there to teach you about prototypes and prototypical inheritance, e.g. this one.

Credit

I’d like to thank the State of Javascript survey and State of JavaScript frameworks for much of the information above! For a few items I used npm-stat to measure popularity. See also this other new survey.

Are you ready to read Part 2?