Part 4: A brief introduction to TypeScript

I said this tutorial was designed for people who had used JavaScript but not TypeScript so I’ll mostly just talk about the main differences between the two, but I will explain a few surprising facts about JavaScript too, in case you only studied a different language, like Java.

TypeScript is based on JavaScript, and the TypeScript compiler (or other tools based on it, like ts-node or ts-jest) translates TypeScript into normal JavaScript simply by stripping out all the type information. Alongside that process, type checking is performed in order to discover type errors - mistakes you’ve made that have something to do with types.

Types can be attached to variables with a colon (:) in their definition, like so:

let z: number = 26;

However you often don’t have to write down the type. For example, if you write

let z = 26;

TypeScript infers that z is a number. So if you write

let z = 26;

z = "Not a number";

You’ll get an error on the second line. TypeScript originally did adopt a loophole though: any variable can be null or undefined:

z = null; // Allowed!

z = undefined; // Allowed!

If you’re new to JavaScript, you’re probably wondering what null and undefined are (or why they are two different things) - well, I promised to tell you about TypeScript and null/undefined are JavaScript things. Ha! But I will say that personally I don’t use null very much; I find convenient to use undefined consistently to avoid worrying about the distinction. undefined is the default value of new variables, and function parameters that were not provided by the caller, and it’s the value you get if you read a property that doesn’t exist on an object. By contrast, JavaScript itself only rarely uses null, so if you don’t use it yourself, you won’t encounter it very often. I’m sure some people do the opposite, and prefer null.

Anyway, many people (including me) are of the opinion that allowing any variable to be null/undefined was a bad idea, so TypeScript 2.0 allows you to take away that permission with the "strictNullChecks": true compiler option in tsconfig.json (or use "strict": true for Maximum Type Checking). Instead you would write

let z: number | null = 26;

if you want z to be potentially null (| means “or”).

Features of TypeScript

Union types

TypeScript has the ability to understand variables that can have multiple types. For example, here is some normal JavaScript code:

var y;

// Math.random() is a random number between 0 and 1

if (Math.random() < 0.5)

y = "Why?";

else

y = 25;

y = [y, y];

console.log(y); // print [25,25] or ["Why?","Why?"] in browser's console

This is allowed in TypeScript by default, because var y (by itself) gives y a type of any, meaning anything. So we can assign any value or object or whatever to y. So we can certainly set it to a string or a number or an array of two things. any is a special type; it means “this value or variable should act like a JavaScript value or variable and, therefore, not give me any type errors.”

I recommend the "strict": true compiler option, but in that mode TypeScript doesn’t allow var y; it requires var y: any instead.

However, TypeScript allows us to be more specific by saying

var y: string | number;

This means “variable y is a string or a number”. If y is created this way, then the if-else part is allowed but the other part that says y = [y, y] is not allowed, because [y, y] is not a string and not a number either (it’s an array of type number[] | string[]). This feature, in which a variable can have one of two (or more) types is called union types and it’s often useful.

Tip: To help you learn TypeScript, it may help to do experiments in the playground.

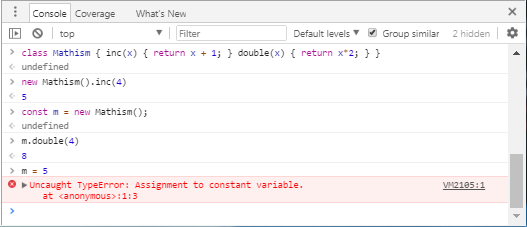

To help you learn more about JavaScript, press F12 in Chrome, Firefox or Edge and look for the Console. In the console you can write JavaScript code, to find out what a small piece of JavaScript does and whether you are writing it correctly:

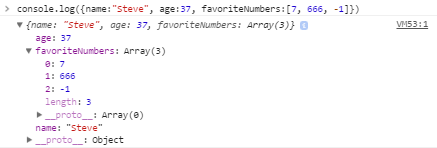

This console is fantastic because you can use it to run experiments in any browser tab. Since TypeScript is just JavaScript with static type checking, you can use the console to help you learn about the part of TypeScript that doesn’t have static types. In your TypeScript file you can call console.log(something) to print things in the browser’s console. In some browsers, log can display complex objects, for example, try writing console.log({name:"Steve", age:37, favoriteNumbers:[7, 666, -1]}):

The help button (F1) isn’t able to look up API documentation, so I recommend searching Mozilla Developer Network for information about built-in JavaScript APIs and browser APIs. Meanwhile, Node.js APIs are documented on nodejs.org.

Classes

As you know, classes are bundles of functions and variables that can be instantiated into multiple objects. Functions inside classes can refer to other functions and variables inside the class, but in JavaScript and TypeScript you must use the prefix this.. A typical JavaScript class might look like this:

class Box {

constructor(width, height) { // initializer

this.width = width;

this.height = height;

}

get area() { return this.width*this.height; } // getter function

setSquare(side) { // normal function

// set the Box's width and height to side, representing a square

this.width = this.height = side;

}

static ZeroSize() { return new Box(0, 0); } // static (class-level) function

}

var big = new Box(1920, 1080);

var mini = new Box(19.2, 10.8);

console.log(`The big box is ${big.area/mini.area} times larger than the minibox`);

console.log(`The area of the zero-size box is ${Box.ZeroSize().area}.`);

The console output is

The big box is 10000 times larger than the small one

The zero-size box has an area of 0.

JavaScript is a little picky: when you create a function outside a class it has the word function in front of it, but when you create a function inside a class, it is not allowed to have the word function in front of it. I don’t know, maybe that’s because functions inside classes are called “methods” instead of functions. Functions and methods are the same thing, except that methods in classes have access to this - a reference to the current object. Except for static methods. static methods are called on the class (e.g. Box.ZeroSize in this example) so they do not have “current object”. (Well, actually the current object of ZeroSize is the Box constructor function, which is not an instance of Box.)

Unlike JavaScript, TypeScript classes allow variable declarations, such as width and height in this example:

class Box {

width: number;

height: number;

constructor(width: number, height: number) {

this.width = width;

this.height = height;

}

get area() { return this.width*this.height; }

setSquare(side: number) {

this.width = this.height = side;

}

static ZeroSize() { return new Box(0, 0); }

}

For convenience, TypeScript lets you define a constructor and the variables it initializes at the same time. So instead of

width: number;

height: number;

constructor(width: number, height: number) {

this.width = width;

this.height = height;

}

you can simply write

constructor(public width: number, public height: number) {}

(If any C# developers are reading this: it works exactly like my LeMP system for C#!)

Unlike JavaScript, TypeScript has private (and protected) variables and functions which are inaccessible outside the class:

class PrivateBox {

constructor(private width: number, private height: number) {}

area() { return this.width * this.height; }

}

let x = new PrivateBox(4, 5);

console.log(x.area()); // OK

console.log(x.width); // ERROR: 'width' is private and only

// accessible within class 'PrivateBox'.

private variables allow you to clearly mark parts of a class as “internal”, things that users of the class should not modify, read, or even think about.

Interfaces

Interfaces are a way of describing “shapes” of objects. Here’s an example:

interface IBox {

readonly width: number;

readonly height: number;

}

interface IArea {

readonly area: number;

}

IBox refers to any class that has a width and height property that are readable numbers, while IArea refers to anything with a readable area property. The Box class satisfies both of these requirements (the get area() function counts as a property, because it is called without () parentheses), and so I could write

let a: IBox = new Box(10,100); // OK

let b: IArea = new Box(10,100); // OK

Interfaces in TypeScript work like interfaces in the Go programming language, not like interfaces in Java and C# - and that’s a good thing. It means that classes don’t have to explicitly say that they implement an interface: Box implements IBox and IArea without saying so. That’s good because it means we can define interfaces for types that originally were not designed for any particular interface. For example, my BTree package defines an IMapSource<Key,Val> interface that represents a read-only dictionary of key-value pairs. The new Map class built into ES6 conforms to this interface so you can put a Map into an IMapSource variable.

readonly means we can read, but not change:

console.log(`The box is ${a.width} by ${a.height}.`); // OK

a.width = 2; // ERR: Cannot assign to 'width' because it is a constant or a read-only property.

Strangely, TypeScript does not require readonly for interface compatibility. For example, TypeScript accepts this code even though it doesn’t work:

interface IArea {

area: number; // area is not readonly, so it can be changed

}

let ia: IArea = new Box(10,100);

ia.area = 5; // Accepted by TypeScript, but causes a runtime error

I think of it as a bug in TypeScript.

TypeScript also has a concept of optional parts of an interface:

interface Person {

readonly name: string;

readonly age: number;

readonly spouse?: Person;

}

For example we can write let p: Person = {name:'John Doe', age:37}. Since p is a Person, we can later refer to p.spouse, which is equal to undefined in this case but could be a Person if a different object were assigned to it that has a spouse. However, you are not allowed to write p = {name:'Chad', age:19, spouse:'Jennifer'} with the wrong data type for spouse (TypeScript explains that “Type string is not assignable to type Person | undefined.”)

Intersection types

Intersection types are the lesser-known cousin of union types. A union type like A | B means that a value can be either an A or a B (but usually not both). An intersection type like A & B means that a value is both A and B at the same time. For instance, this box is both IBox and IArea, so it has all the properties from both interfaces:

let box: IBox & IArea = new Box(5, 7);

If you ever mix union and intersection types, you can use parentheses to change the meaning:

// either a Date&IArea or IBox&IArea

let box1: (Date | IBox) & IArea = new Box(5, 7);

// either a Date or an IBox&IArea

let box2: Date | (IBox & IArea) = new Box(5, 7);

& has higher precedence than |, so A & B | C means (A & B) | C.

Structural types

In some other programming languages, every type has a name, such as string or double or Component. In TypeScript, many types do have names but, more fundamentally, most types are defined by their structure. In other words, the type’s name, if it even has one, is not important to the type system. Here’s an example where variables have a structural type:

var book1 = { title: "Adventures of Tom Sawyer", year:1876 };

var book2 = { title: "Adventures of Huckleberry Finn", year:1884 };

If you hover your mouse over book1 in VS Code, its type is described as { title: string; year: number; }. This is a “structural” type: a type defined entirely by the fact that it has a property called title which is a string, and another property called year which is a number. Thus book1 and book2 have the same type and you can assign one to the other, or to a different book.

book1 = book2; // allowed

book2 = { year: 1995, title: "Vertical Run" }; // allowed

Generally speaking you can assign a value with “more stuff” to a variable whose type includes “less stuff”, but not the other way around:

var book3 = { title: "The Duplicate", author: "William Sleator", year:1988 };

var book4 = { title: "The Boy Who Reversed Himself" };

book1 = book3; // allowed

bool1 = bool4; /* NOT allowed. Here is the error message:

Type '{ title: string; }' is not assignable to type '{ title: string;

year: number; }'. Property 'year' is missing in type '{ title: string; }'.

*/

In addition if we have an interface like this:

interface Book {

title: string;

author?: string;

year: number;

}

Then we can assign any Book value to any of these book variables (except book3, because the author is required in book3 and Book might not contain an author), and we can assign any of the book variables to a new variable of type Book (except book4, of course).

Clearly, structural types are fantastic. This is obvious after you spend a few years using languages without them. For example, imagine if two people, Alfred and Barbara, write different modules A and B. They both deal with points using X-Y coordinates. So each module contains a Point interface:

interface Point {

x: number;

y: number;

}

Many languages use “nominal” types instead of structural types, and in these languages A.Point is considered to be a completely different type than B.Point even though they are identical. So any points produced by A cannot be used by B and vice versa. This is frustrating and stupid, so please take a moment to celebrate with me the wonder of TypeScript’s structural typing.

Structural types can be written either with semicolons or commas, e.g. { x: number, y: number } and { x: number; y: number; } are the same.

Flow-based typing (and the exclamation mark)

If s is a string, you could write s.match(/[0-9]+/) to find the first group of digits in that string. /[0-9]+/ is a RegExp - an object that can be used to search strings using Regular Expressions. Regular expressions are a string-matching system supported by many programming languages including JavaScript.

match returns an array of strings, or null if the RegExp did not match the string. For example, if s = "I have 10 cats and 2 dogs" then s.match(/[0-9]+/) returns ["10"], but if s = "I have ten velociraptors and a weevil" then match returns null.

If you were looking for digits in a string, you’d want your code to behave differently depending on whether the string has digits or not, right? So you’d use an if statement:

var found: string[]|null = s.match(/[0-9]+/);

if (found) {

console.log("The string has a number in it: " + found[0]);

} else {

console.log("The string lacks digits.");

}

As you probably know, if (found) means “if found is truthy”. It basically means if (found != null && found != 0 && found != false).

If you don’t check whether found !== null, TypeScript will give you an error:

var found = s.match(/[0-9]+/);

console.log("The string has a number in it: " + found[0]);

// Error: Object is possibly 'null' ^^^^^

So why don’t you get an error when you use the if statement? That’s the magic of TypeScript’s flow-based typing. In the first branch of the if statement, TypeScript knows that found cannot be null, and so the type of found changes within that block to exclude null. Thus, its type becomes string[]. Similarly, inside the else {...} block, TypeScript knows that found cannot be string[], so string[] is excluded and the type of found becomes null in that region.

But TypeScript has a ! exclamation-mark operator which is used to avoid certain error messages. It means “look, compiler, I know you think this variable could be null or undefined, but I promise you it isn’t. So if found has type string[]|null, found! has type string[]. So if you’re sure that s has digits in it, you can use ! to avoid the error message:

var found = s.match(/[0-9]+/);

console.log("The string has a number in it: " + found![0]);

TypeScript’s flow-based typing system supports the typeof and instanceof operators, as well as ordinary comparison operators. So if you start with a variable that could have several types, you can use any of these operators to narrow down the type.

function whatAmI(thing: string|RegExp|null|number[]|Date) {

if (thing instanceof RegExp || typeof thing === "string") {

// Here, TypeScript knows that thing is RegExp|string

if (typeof thing !== "string")

console.log("Ahh, so it's a RegExp: " + thing.toString());

else

console.log("It's a string of length " + thing.length);

} else {

// Here, TypeScript knows that thing is null|number|Date

if (thing == null)

console.log("Aha! You just gave me a null.");

else if (Array.isArray(thing))

console.log("Oh, it's an array of numbers: " +

thing.map(n => n.toPrecision(3)).join(", "));

else

console.log("So, it's a date in " + thing.getFullYear());

}

}

Note: In case you haven’t heard, JavaScript has a funky distinction between “primitive” and “boxed primitive” types (which are objects). For example, "yarn" is a primitive, and its type is string. However there is also a boxed string type called String with a capital S, which is rarely used. You can create a String by writing new String("yarn"). The thing to keep in mind is that these are totally different types. "yarn" instanceof String is false: "yarn" is a string, not a String! "yarn" instanceof string is not false; instead it’s a totally illegal expression (because the right-hand side of instanceof must be a constructor function and string does not have a constructor).

JavaScript provides two different operators for testing the types of primitives and objects (i.e. non-primitives). instanceof checks the prototype chain to find out if a value is a certain kind of object; typeof checks whether something is a primitive and if so, what kind. As you can see in the code above, instanceof is a binary operator that returns a boolean, while typeof is a unary operator that returns a string. For example, typeof "yarn" returns "string" and typeof 12345 returns "number". The primitive types are number, boolean, string, symbol, undefined, and null. Everything that is not a primitive is an “object” Object, including functions, but typeof treats functions specially (e.g. typeof Math.sqrt === "function" and Math.sqrt instanceof Object === true). Symbols are new in ES6, and although null is a primitive, typeof null === "object" by mistake.

As you can see in the example above, TypeScript also understands Array.isArray as a way to detect an array. However, some other methods of detecting types in JavaScript are not supported:

if (thing.unshift)is sometimes used to distinguish strings from other things, because almost nothing except strings have anunshiftmethod. This is not supported in TypeScript because you are not allowed to read a property that may not exist.if (thing.hasOwnProperty("unshift"))isn’t recognized as a type test.if (thing.constructor === String)isn’t recognized as a type test (in JavaScript, reading a property such asconstructorpromotesthingto Boxed status, so even ifthingis a primitive string, its.constructorwill be non-primitive.)if ("unshift" in thing)doesn’t work. I don’t know why, but “the right-hand side of an ‘in’ expression must be of type ‘any’, an object type or a type parameter.” (inshould be avoided anyway because it is slow.)

Type aliases

The type statement creates a new name for a type; for example after writing

type num = number;

You can use num as a synonym for number. type is similar to interface since you can write something like this…

type Point = {

x: number;

y: number;

}

…instead of interface Point {...}. However, only interfaces support inheritance; for example I can create a new interface that is like Point but also has a new member z, like this:

interface Point3D extends Point {

z: number;

}

You can’t do inheritance with type (however if Point was defined with type, you are still allowed to extend it with an interface).

Function types

In JavaScript you can pass functions to other functions, like this:

function doubler(x) { return x*2; }

function squarer(x) { return x*x; }

function experimenter(func)

{

console.log(`When I send 5 to my function, ${func(5)} comes out.`);

}

experimenter(doubler);

experimenter(squarer);

Output:

When I send 5 to my function, 10 comes out.

When I send 5 to my function, 25 comes out.

In TypeScript you normally need to write down the types of function arguments, which means you need to know how to express the type of func. As you can see here, its type should be something like (param: number) => number:

function doubler(x: number) { return x*2; }

function squarer(x: number) { return x*x; }

function experimenter(func: (param: number) => number)

{

console.log(`When I send 5 to my function, ${func(5)} comes out.`);

}

experimenter(doubler);

experimenter(squarer);

TypeScript requires you to give a name to the parameter of func, but it doesn’t matter what that name is. I could have called it x, or Wednesday, or myFavoriteSwearWord and it would have made no difference whatsoever. But don’t even think of calling it asshat. The compiler won’t care, but what about your boss? Better safe than sorry, that’s all I can say.

In JavaScript, everything inside an object is a “property” (a kind of variable), and that includes functions. As a consequence, these two interfaces mean the same thing:

interface Thing1 {

func: (param: number) => number;

}

interface Thing2 {

func(param: number): number;

}

And so this code is allowed:

class Thing {

func(x: number) { return x * x * x; }

}

let t1: Thing1 = new Thing();

let t2: Thing2 = t1;

Does it seem weird to you that TypeScript requires : before the return type of a “normal” function but it requires => before the return type of a function variable? Anyway, that’s the way it is.

Generics (and Dates, and stuff)

Let’s say I write a function that ensures a value is an array, like this:

function asArray(v: any): any[] {

// return v if it is an array, otherwise return [v]

return (Array.isArray(v) ? v : [v]);

}

The asArray function works, but it loses type information. For example what if this function calls it?

/** Prints one or more dates to the console */

function printDates(dates: Date|Date[]) {

for (let date of asArray(dates)) {

// SUPER BUGGY!

var year = date.getYear();

var month = date.getMonth() + 1;

var day = date.getDay();

console.log(`${year}/${month}/${day}`);

}

}

The TypeScript compiler accepts this code, but it has two bugs. The code correctly added 1 to the month (because getMonth() returns 0 for January and 11 for December), but the code for getting the Year and Day are both wrong. Since asArray returns any[], however, type checking and IntelliSense, which could have caught these bugs, is disabled on date. These bugs could have been avoided if asArray were generic:

function asArray<T>(v: T | T[]): T[] {

return Array.isArray(v) ? v : [v];

}

This version of asArray does the same thing, but it has a type parameter, which I have decided to call T, to enable enhanced type checking. The type parameter can be any type, so it is similar to any, but it enables the function to describe the relationship between the parameter v and the return value. Specifically, it says that v and the return value have, well, similar types. When you call asArray, the TypeScript compiler finds a value of T that allows the call to make sense. For example, if you call asArray(42) then the compiler chooses T=number because it is possible to use 42 as an argument to asArray(v: number|number[]): number[]. After choosing T=number, TypeScript realizes that asArray returns an array of numbers.

In printDates we called asArray(dates) and the compiler figures out that T=Date works best in that situation. After choosing T=Date, TypeScript realizes that asArray returns an array of Date. Therefore, the variable date has type Date, and then it finds the first bug: date.getYear does not exist! Well, actually it does exist, but it has been deprecated due to its strange behavior (it returns the number of years since 1900, i.e. 118 in 2018). Instead you should call getFullYear.

TypeScript itself doesn’t notice the second bug, but when you type date.getDay, VS Code will inform you in a little popup box that this function “Gets the day of the week, using local time”. The day of the week? You have got to be kidding me!

Thanks to generics and VS Code, we fix our code to call date.getDate instead, which of course does not return the date without a time attached to it (like any sensible person would think) but rather the day of the current month. Unlike the month, the day does not start counting from zero.

/** Prints one or more dates to the console */

function printDates(dates: Date|Date[]) {

for (let date of asArray(dates)) {

var year = date.getFullYear();

var month = date.getMonth() + 1;

var day = date.getDate();

console.log(`${year}/${month}/${day}`);

}

}

Meanwhile, you start to wonder whether Date has more pitfalls you should be aware of and which moron designed the Date class in the first place. The answers are “yes” and “Brendan Eich slavishly copied Date’s horrible design from Java 1.0”.

One good thing about Dates is that they are normally stored in UTC (universal time zone a.k.a. GMT). This means that if the user changes the time zone on their computer, the Date objects in your program continue to represent the same point in time, but the string returned by .toString() changes. Usually this is what you want, especially in JavaScript where you might have client and server code running in different time zones.

An advanced example of generics appears in my simplertime module. In this case I had a timeToString function that accepted a list of formatting options like this:

export interface TimeFormatOptions {

/** If true, a 24-hour clock is used and AM/PM is hidden */

use24hourTime?: boolean;

/** Whether to include seconds in the output (null causes seconds

* to be shown only if seconds or milliseconds are nonzero) */

showSeconds?: boolean|null;

...

}

export function timeToString(time: Date|number, opt?: TimeFormatOptions): string {

...

}

The export keyword is used for sharing code to other source files. For example you can import timeToString in your own code using import {timeToString} from 'simplertime' (after installing with npm i simplertime of course). If you want to import things from a different file in the same folder, add a ./ prefix on the filename, e.g. import * as stuff from './mystuff'.

Generics can also be used on classes and interfaces. For example, JavaScript has a Set type for holding an unordered collection of values. We might use it like this:

var primes = new Set([2, 3, 5, 7]);

for (var i = 0; i < 10; i++)

console.log(`Is the number ${i} prime? ${primes.has(i)}`);

In TypeScript, though, Set has a type parameter, Set<T>, meaning that all items in the set have type T. In this code TypeScript infers that T=number, so if you write primes.add("hello!") you’ll get a Type Error. If you actually want to create a set that can hold both strings and numbers, you can do it like this:

var primes = new Set<string|number>([2, 3, 5, 7]);

You can also create your own generic types. For example, I created a B+ Tree data structure called BTree<K, V>, which is a collection of key-value pairs, sorted by key, that supports fast cloning. It has two type parameters, K (a key) and V (a value) and its definition looks roughly like this (function bodies have been omitted because I just want to show you how a generic class looks):

// Type parameters can have default values,

// so `var t: BTree` means `var t: BTree<any,any>`

export class BTree<K=any, V=any>

{

// Root node (key-value pairs are stored in here)

private _root: BNode<K, V>;

// Total number of items in the collection

_size: number = 0;

// Maximum number of items in a single node

_maxNodeSize: number;

// This function must return less-than-0 if a<b and above-zero if a>b

_compare: (a:K, b:K) => number;

public constructor(entries?: [K,V][],

compare?: (a: K, b: K) => number,

maxNodeSize?: number) { ... }

get size() { return this._size; }

clear() { ... }

get(key: K): V | undefined { ... }

set(key: K, value: V, overwrite?: boolean): boolean { ... }

has(key: K): boolean { ... }

delete(key: K) { ... }

/** Quickly clones the tree by marking the root node as shared.

* Both copies remain editable. When you modify either copy, any

* nodes that are shared (or potentially shared) between the two

* copies are cloned so that the changes do not affect other copies.

* This is known as copy-on-write behavior, or "lazy copying". */

clone(): BTree<K,V> { ... }

...

}

Literals as types

Remember how there is an error when you write this?

let z = 26;

z = "Zed";

The error message sounds a bit strange:

Type '"Zed"' is not assignable to type 'number'

Why does it say that "Zed" is a “type”, instead of a “value” or a “string”? In order to understand this, it is necessary to understand that TypeScript has an ability to treat values as types. "Zed" is a string, of course, but it’s more than that; it has another type at the same time, a type called "Zed" which represents the value “Zed”. We can even create a variable with this type:

let zed: "Zed" = "Zed";

Now we have created a completely useless variable called zed. We can set this variable to “Zed”, but nothing else:

zed = "Zed"; // OK

zed = "ZED"; // Error: Type '"ZED"' is not assignable to type '"Zed"'.

By default we can set zed to null and undefined, but luckily with "strictNullChecks": true we can close that loophole so that this variable will never be anything except “Zed”. Thank God for that, is all I can say.

So what are these literal-types good for? Well, sometimes a function allows only certain particular strings. For example, imagine if you have a function that lets you turn("left") or turn("right") but nothing else. This function could be declared with a literal-type:

function turn(direction: "left"|"right") { ... }

Fixed-length arrays

Here’s another puzzle for you: what’s the difference between the types number[] and [number]? The first one is an array of numbers; the second is an array that contains only one element, which is a number.

You see, TypeScript supports arrays of a specific length, in which each element of the array can have a different type. These fixed-length array types are called tuples. For example, [string,number] denotes an array of length 2 with the first element being a string and the second being a number. In addition, this array has a property length: 2, i.e. its type is 2, not just number. These fixed-length arrays are called tuple types.

Advanced generics

So, remember the simplertime module I was talking about? It also exports a defaultTimeFormat object which holds default values for the timeToString formatting options. I wanted to define a special function which would allow me to write things like get(options, 'use24hourTime') to retrieve the value of options.use24hourTime if it exists and defaultTimeFormat.use24hourTime if it does not exist. In many languages it is impossible to write a function like that, but it is possible in “dynamic” languages such JavaScript. Here’s how the get function would look like in JavaScript:

function get(opt, name) {

if (opt === undefined || opt[name] === undefined)

return defaultTimeFormat[name]

return opt[name];

}

In JavaScript and TypeScript, thing.property can be written as thing["property"] instead and if the property does not exist, the result is undefined. But in the square-bracket version we can use a variable, so that the question “which property are we using?” can be answered by code located elsewhere.

Translating this to TypeScript is possible with a feature called keyof, but it’s very tricky. Here is the translation:

function get<K extends keyof TimeFormatOptions>(

opt: TimeFormatOptions|undefined, name: K): TimeFormatOptions[K] {

if (opt === undefined || opt[name] === undefined)

return defaultTimeFormat[name]

return opt[name];

}

Here, the type variable K has a constraint attached to it, K extends keyof TimeFormatOptions. Here’s how it works:

keyof Xturns the properties ofXinto a union type of the names of the properties. For example, given theBookinterface from earlier,keyof Bookmeans"title" | "author" | "age". Likewisekeyof TimeFormatOptionsis any of the strings inTimeFormatOptions.- The “extends” constraint,

X extends Y, means that “X must be Y, or a subtype of Y”. For exampleX extends Objectmeans thatXmust be some kind ofObject, which means it can be an array or aDateor even a function, all of which are considered to be Objects, but it can’t be astringor anumberor aboolean. SimilarlyX extends Pointmeans thatXisPointor a more specific type thanPoint, such asPoint3D. - What would

B extends keyof Bookmean? It would mean thatBis a subtype of"title" | "author" | "age". And remember that we are talking about types here, not values. The string literal"title"has the value"title"but it also has the type"title", which is a different concept. The type is handled by the TypeScript type system, the value is handled by the JavaScript. The"title"type no longer exists when the program is running but the"title"value still does. Now,Bcan be assigned to types like"title"or"title" | "age", because every value of type"title" | "age"(or “title”) can be assigned to a variable of typekeyof Book. HoweverBcannot bestring, because some strings are not “title”, “author” or “age”. - Similarly,

Kis constrained to have a subtype ofkeyof TimeFormatOptions, such as"use24hourTime". - The type

X[Y]means “the type of the Y property of X, where Y is a number or string literal”. For example, the typeBook["author"]isstring | undefined.

Putting this all together, when I write get(options, 'use24hourTime'), the compiler decides that K='use24hourTime'. Therefore, the name parameter has type "use24hourTime" and the return type is TimeFormatOptions["use24hourTime"], which means boolean | undefined.

Holes in the type system

Since TypeScript is built on top of JavaScript, it accepts some flaws in its type system for various reasons. Earlier we saw one of these flaws, the fact that this code is legal:

class Box {

constructor(public width: number, public height: number) {}

get area() { return this.width*this.height; }

}

interface IArea {

area: number; // area is not readonly

}

let ia: IArea = new Box(10,100);

ia.area = 5; // Accepted by TypeScript, but causes a runtime error

Here are some other interesting loopholes:

You can assign a derived class to a base class

A Date is a kind of Object so naturally you can write

var d: Object = new Date();

So it makes sense that we can also assign this D interface to this O interface, right? Well, no, not really:

interface D { date: Date }

interface O { date: Object }

var de: D = { date: new Date() }; // okay...

var oh: O = de; // makes sense...

oh.date = { date: {wait:"what?"} } // wait, what?

TypeScript now believes de.date is a Date when it is actually an Object.

You can assign [A,B] to (A|B)[]

It makes sense that an array of two items, an A followed by a B, is also a an array of A|B, right? Actually, no, not really:

var array1: [number,string] = [5,"five"];

var array2: (number|string)[] = array1; // makes sense...

array2[0] = "string!"; // wait, what?

TypeScript now believes array1[0] is a number when it is actually a string. This is an example of a more general problem, that arrays are covariant but shouldn’t be. You can put an array of Date in an variable of type Object[] but this is unsafe. Fun fact: Java and C# have the same problem.

Arrays? There be dragons.

In the recommended strict mode, you can’t put null or undefined in arrays of numbers…

var a = [1,2,3];

a[3] = undefined; // Type 'undefined' is not assignable to type 'number'

So that means when we get a value from an array of numbers, it’s a number, right? Actually, no, not really:

var array = [1,2,3];

var n = array[4];

TypeScript now believes n is a number when it is actually undefined.

A more obvious hole is that you can allocate a sized array of numbers… with no numbers in it:

var array = new Array<number>(2); // array of two "numbers"

var n:number = array[0];

Function parameters are bivariant when overriding

Unlike other languages with static typing, TypeScript allows overriding with covariant parameters. “Covariant parameter” means that as the class gets more specific (A to B), the parameter also gets more specific (Object to Date):

class A {

method(value: Object) { }

}

class B extends A {

method(value: Date) { console.log(value.getFullYear()); }

}

var a:A = new B();

a.method({}); // Calls B.method, which has a runtime error

This is unsafe, but oddly it is allowed. In contrast, it is (relatively) safe to override with contravariant parameters, like this:

class A {

method(value: Date) { }

}

class B extends A {

method(value: Object) { console.log(value instanceof Date); }

}

Covariant return types are also safe:

class A {

method(): Object { return {} }

}

class B extends A {

method(): Date { return new Date(); }

}

TypeScript rightly rejects contravariant return types:

class A {

method(): Date { return new Date(); }

}

class B extends A {

// Property 'method' in type 'B' is not assignable to the same property in base type 'A'.

// Type '() => Object' is not assignable to type '() => Date'

// Type 'Object' is not assignable to type 'Date'

method(): Object { return {} }

}

Classes think they are interfaces (but they’re not)

TypeScript allows you to treat a class as though it were an interface. For example, this is legal:

class Class {

content: string = "";

}

var stuff: Class = {content:"stuff"};

Stuff isn’t a real Class, but TypeScript thinks it is, which can cause a runtime TypeError if you use instanceof Class somewhere else in the program:

function typeTest(x: Class|Date) {

if (x instanceof Class)

console.log("The class's content is " + x.content);

else

console.log("It's a Date in the year " + x.getFullYear());

}

typeTest(stuff);

this isn’t necessarily what you think

This is a loophole of JavaScript, not TypeScript, but any time a function uses this, it might be accessing some completely unexpected object, with a different type than you think:

class Time {

constructor(public hours: number, public minutes: number) { }

toDate(day: Date) {

var clone = new Date(day);

clone.setHours(this.hours, this.minutes);

return clone;

}

}

// Call toDate() with this=12345

Time.prototype.toDate.call(12345, new Date());

TypeScript’s only sin is that it won’t try to stop you from doing this.

Speaking of this, one thing JavaScript developers should know is that arrow functions like x => x+1 work slightly differently than anonymous functions like function(x) {return x+1}. Arrow functions inherit the value of this from the outer function in which they are located, but normal functions receive a new value of this from the caller. So if f is an arrow function, f.call(12345, x) doesn’t change this, so it like calling f(x). That’s usually a good thing, but if you write

var obj = { x: 5, f: () => this.x }

You should realize that obj.f() does not return obj.x.

Lessons

To avoid these holes, you need to

- Not treat an object as a “baser” type (e.g. don’t treat

Das anO) unless you are sure that the baser type won’t be modified in a way that could violate the type system. - Don’t cast an array to a “baser” type (e.g. don’t treat

D[]asO[], or[A,B]as(A|B)[]) unless you are sure that the baser type won’t be modified in a way that could violate the type system. - Be careful not to leave any “holes” with undefined values in your arrays.

- Be careful not to use out-of-bounds array indexes.

- Not override a base-class method with covariant parameters.

- Avoid treating a class

Kas though it were an interface, unless you are sure that no code will ever check the type withinstanceof. - Avoid using

.call(...)

TypeScript actually had more holes in the past, which are now fixed.

JSX

React introduced the concept of JSX code. Or maybe Hyperscript introduced it and React copied the idea soon afterward. In any case, JSX looks like HTML/XML code, but you are not making DOM elements, you’re making plain-old JavaScript objects, which we call a “virtual DOM”. For example <img src={imageUrl}/> actually means React.createElement("img", { src: imageUrl }) in a .jsx or .tsx file.

If JSX is a React thing, why am I talking about it in the TypeScript section? Because support for JSX is built into the TypeScript compiler. To get JSX support in any TypeScript file, you just have to change the file’s extension from .ts to .tsx.

JSX can be used in the same places as normal expressions: you can pass JSX code to a function…

ReactDOM.render(<h1>I'm JSX code!</h1>, document.body);

you can store it in a variable…

let variable = <h1>I'm JSX code!</h1>;

and you can return it from a function…

return <h1>I'm JSX code!</h1>;

Because <h1>I'm JSX code!</h1> really just means React.createElement("h1", null, "I'm JSX code!").

It is important whether a JSX tag starts with a capital letters; it is translated to TypeScript (or JavaScript) differently if it does. For example,

<div class="foo"/>meansReact.createElement('div', {"class":"foo"}), but<Div class="foo"/>meansReact.createElement(Div, {"class":"foo"})(without quotes aroundDiv).

You can also use a “complex” component name with dots or even type parameters, e.g. <module.Component/> or <Thing<number>>12345</Thing>. If the tag contains a dot, TypeScript assumes that it refers to a component even if the name is in lowercase.

Tips for using JSX:

- JSX is XML-like, so all tags must be closed: write

<br/>, not<br>. - JSX only supports string attributes and JavaScript expressions. When writing numeric attributes in TypeScript, use

<input type="number" min={0} max={100}/>, becausemax=100is a syntax error andmax="100"is a type error. - In React/Preact, you can use an array of elements in any location where a list of children are expected. For example, instead of

return <p>Ann<br/>Bob<br/>Cam</p>, you can writelet x = [<br/>, 'Bob', <br/>]; return <p>Ann{x}Cam</p>. This has the same effect because React/Preact “flattens” arrays in the child list. - In React, the

classattribute is not supported for some reason. UseclassNameinstead. - JSX itself does not support optional property or children. For example, suppose you write

<Foo prop={x}>but you want to omit thepropwhenxisundefined. Well, JSX itself doesn’t support anything like that. However, most components treat anundefinedproperty the same as a missing property, so it usually works anyway. JSX doesn’t support optional children either, but you can get the same effect with an empty array: because arrays are “collapsed” by React/Preact,<Foo>{ [] }</Foo>has the same effect as<Foo></Foo>.<Foo>{undefined}</Foo>does not have this effect (you end up with a single child equal toundefined.) - If you have an object like

obj = {a:1, b:2}and you would like to use all the properties of the object as properties of a Component, you can write<Component {...obj}/>. The dots are always required, as<Component {obj}/>is meaningless.

At the top of the file, the @jsx pragma can control the “factory” function that is called to translate JSX elements. For example if you use /** @jsx h */ then <b>this</b> translates to h('b', null, "this") instead of React.createElement('b', null, "this"). Some Preact apps use this pragma (h is the preact function to create elements), but you won’t need to use it in this tutorial (createElement is a synonym for h in preact). Also, in tsconfig.json you can get the same effect with "jsxFactory": "h" in the compilerOptions.

See also

- TypeScript evolution: excellent documentation of the newer TypeScript features

Next

See Part 5 to start learning about React!